Builders and Defenders

History of Fort Negley

The Builders and Defenders Database centers the lives of the enslaved and free Black builders and defenders of the Civil War Fort Negley in Nashville, Tennessee.

During the Civil War, the nation stood divided. Tennessee, the last state to attempt to leave the Union, became a focal point for a national leadership determined to preserve it. In 1862, federal forces moved to occupy its capital, Nashville.

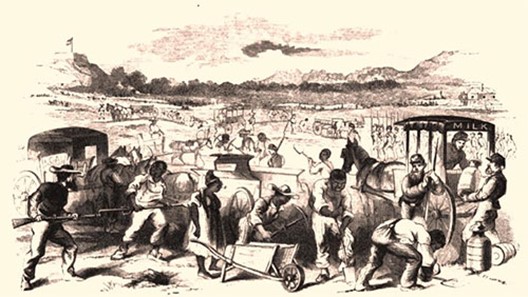

The Union military was instructed to construct a system of ambitious and impervious defenses and wartime infrastructure to create a stronghold from which to repel Confederate forces and bring the war to its end. St. Cloud Hill, one of the most elevated points surrounding the city of Nashville, was singled out as the location to build the largest inland stone fortification of the war: Fort Negley.

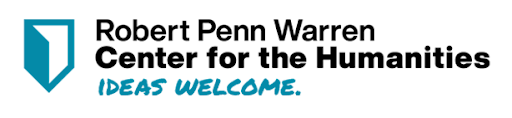

Such an endeavor required a larger workforce than the military could provide on its own, and as was precedent in other places, military leaders agreed that Nashville’s enslaved and free Black populations should become the builders. Many of the enslaved people, like James Harding Sr. went willingly. They self-emancipated, leaving their enslavers in the dead of night and running toward the Union soldiers’ campfires. Others found themselves “loaned out” by enslavers eager to demonstrate collaboration with the occupying forces and hopeful of monetary gain. Others still, like Ruffin and Egbert Bright, were coerced, rounded up from plantations, homes, and churches by Union officers assigned to the loathsome task. Another group of laborers were from Middle Tennessee’s population of freedmen, negotiating a wage in exchange for skilled work.

The Builders and Defenders Database centers the lives of the enslaved and free Black builders and defenders of the Civil War Fort Negley in Nashville, Tennessee.

During the Civil War, the nation stood divided. Tennessee, the last state to attempt to leave the Union, became a focal point for a national leadership determined to preserve it. In 1862, federal forces moved to occupy its capital, Nashville.

The Union military was instructed to construct a system of ambitious and impervious defenses and wartime infrastructure to create a stronghold from which to repel Confederate forces and bring the war to its end. St. Cloud Hill, one of the most elevated points surrounding the city of Nashville, was singled out as the location to build the largest inland stone fortification of the war: Fort Negley.

Such an endeavor required a larger workforce than the military could provide on its own, and as was precedent in other places, military leaders agreed that Nashville’s enslaved and free Black populations should become the builders. Many of the enslaved people, like James Harding Sr. went willingly. They self-emancipated, leaving their enslavers in the dead of night and running toward the Union soldiers’ campfires. Others found themselves “loaned out” by enslavers eager to demonstrate collaboration with the occupying forces and hopeful of monetary gain. Others still, like Ruffin and Egbert Bright, were coerced, rounded up from plantations, homes, and churches by Union officers assigned to the loathsome task. Another group of laborers were from Middle Tennessee’s population of freedmen, negotiating a wage in exchange for skilled work.

Together, this group of builders worked day and night on Nashville’s defenses under extreme conditions. It is said that approximately 2,700 worked on Fort Negley, though the truth is a little more nebulous. A total of 4,933 enslaved and free Black laborers worked with the Union military on Nashville’s defenses, moving from location to location as needed to create a connected system of forts surrounding Fort Andrew Johnson (the TN Capitol building): Fort Negley, Fort Houston (Music Row Roundabout), Fort Casino (City Reservoir), Fort Morton (Rose Park), and Fort Gillem (Jubilee Hall, Fisk University). The builders’ names and biographical information appear in this database. The vast majority of the laborers were men, but some women and children took part in the fort's construction. Moses McGavock, whose family was enslaved by the prominent planter family, the McGavocks, was the youngest at the age of just twelve.

Major General Stearns, the Commissioner for the Organization of the USCT in Middle and East Tennessee later recounted the work hazards encountered by the builders in the Boston Liberator: “These men, working in the heat of the Autumn months, lying on the hillside at night in the heavy dews without shelter, and fed with poor food, soon sickened. In four months about 800 of them died; the remainder were kept at work from six to fifteen months without pay.” Many were promised ten dollars a month but most were never paid (the ledger of the few who did get paid are also in this database).

When the builders were done with Fort Negley and the other wartime defenses, Nashville became a fortified stronghold, second only to Washington D.C. Many of the surviving male laborers who had worked on Fort Negley joined the 12th regiment of the United States Colored Troops. Some joined voluntarily, and others were forced to join. The 12th was one of eight regiments of the USCT that fought alongside white regiments at the various encounters of the Battle of Nashville to protect the city. (The soldiers of all eight regiments—12th, 13th, 14th, 16th, 17th, 18th, 44th, and 100th are in the database, and those of the 12th have the richest information available).

Together, this group of builders worked day and night on Nashville’s defenses under extreme conditions. It is said that approximately 2,700 worked on Fort Negley, though the truth is a little more nebulous. A total of 4,933 enslaved and free Black laborers worked with the Union military on Nashville’s defenses, moving from location to location as needed to create a connected system of forts surrounding Fort Andrew Johnson (the TN Capitol building): Fort Negley, Fort Houston (Music Row Roundabout), Fort Casino (City Reservoir), Fort Morton (Rose Park), and Fort Gillem (Jubilee Hall, Fisk University). The builders’ names and biographical information appear in this database. The vast majority of the laborers were men, but some women and children took part in the fort's construction. Moses McGavock, whose family was enslaved by the prominent planter family, the McGavocks, was the youngest at the age of just twelve.

Major General Stearns, the Commissioner for the Organization of the USCT in Middle and East Tennessee later recounted the work hazards encountered by the builders in the Boston Liberator: “These men, working in the heat of the Autumn months, lying on the hillside at night in the heavy dews without shelter, and fed with poor food, soon sickened. In four months about 800 of them died; the remainder were kept at work from six to fifteen months without pay.” Many were promised ten dollars a month but most were never paid (the ledger of the few who did get paid are also in this database).

When the builders were done with Fort Negley and the other wartime defenses, Nashville became a fortified stronghold, second only to Washington D.C. Many of the surviving male laborers who had worked on Fort Negley joined the 12th regiment of the United States Colored Troops. Some joined voluntarily, and others were forced to join. The 12th was one of eight regiments of the USCT that fought alongside white regiments at the various encounters of the Battle of Nashville to protect the city. (The soldiers of all eight regiments—12th, 13th, 14th, 16th, 17th, 18th, 44th, and 100th are in the database, and those of the 12th have the richest information available).

To support the army, the US Navy sent seven federal gunboats down the Cumberland River in the winter of 1864 to clear out chokepoints, weaken the Confederate military, and help shore up the city’s defenses. Black sailors like Nashville-born Michael Rainer and Frank Twiggs onboard the USS Reindeer worked alongside white sailors to open supply lines and repel Confederate troops. The boats which aided the Union soldiers in the Battle of Nashville were the USS Neosho, USS Brilliant, USS Carondelet, USS Cairo, USS Moose, USS Fairplay, USS Reindeer, USS Silver Lake, and the USS Springfield (the names, birthplaces, muster information, and vessel assignments of the 174 Black sailors onboard those gunboats can be found in the database).

The Battle of Nashville saw the most African American involvement out of any Civil War Battle. Soldiers like Private Peter Bailey of the 17th Regiment, Company K, fought at Granbury’s Lunette and Peach Orchard Hill, suffering tremendous losses because they had not received sufficient training equal to their white counterparts. Despite this, they fought fiercely and repelled General Hood’s army, effectively ending the war in Tennessee and permanently weakening Confederate forces. Thanks to their contributions, the Civil War ended shortly after.

To support the army, the US Navy sent seven federal gunboats down the Cumberland River in the winter of 1864 to clear out chokepoints, weaken the Confederate military, and help shore up the city’s defenses. Black sailors like Nashville-born Michael Rainer and Frank Twiggs onboard the USS Reindeer worked alongside white sailors to open supply lines and repel Confederate troops. The boats which aided the Union soldiers in the Battle of Nashville were the USS Neosho, USS Brilliant, USS Carondelet, USS Cairo, USS Moose, USS Fairplay, USS Reindeer, USS Silver Lake, and the USS Springfield (the names, birthplaces, muster information, and vessel assignments of the 174 Black sailors onboard those gunboats can be found in the database).

The Battle of Nashville saw the most African American involvement out of any Civil War Battle. Soldiers like Private Peter Bailey of the 17th Regiment, Company K, fought at Granbury’s Lunette and Peach Orchard Hill, suffering tremendous losses because they had not received sufficient training equal to their white counterparts. Despite this, they fought fiercely and repelled General Hood’s army, effectively ending the war in Tennessee and permanently weakening Confederate forces. Thanks to their contributions, the Civil War ended shortly after.

After reunification, many of the Union Civil War veterans were assigned to these federal fortifications during Reconstruction to keep the peace and enforce their fragile and hard-won freedoms. Many formerly enslaved people flocked near the forts to remain under the protection of the Black soldiers. They formed or joined historically Black neighborhoods and organizations as they self-reconstructed and drafted plans for recovery from centuries of enslavement.

One of these neighborhoods was called Bass Street. Located between the Edgehill and Cameron-Trimble neighborhoods at the foot of St. Cloud Hill between Fort Negley and the city, the Bass Street Community was formed by Black Civil War veterans and their families and other refugees from enslavement. Like most postwar communities, the residents embraced the ideals of community. Many worked at the Tennessee Central Railway (you’ll find some of their information from TCR employment records in the database) and enrolled their children in the nearby Pearl Jr. High (renamed the Cameron school in 1928) or at Fisk University. They worshiped at the Bass Street Church, which they had built together with their own hands. This church still exists today in its third location on Brick Church Pike in Northeast Nashville. Several of the Bass Street descendants who attended the original church as children remain members today.

After reunification, many of the Union Civil War veterans were assigned to these federal fortifications during Reconstruction to keep the peace and enforce their fragile and hard-won freedoms. Many formerly enslaved people flocked near the forts to remain under the protection of the Black soldiers. They formed or joined historically Black neighborhoods and organizations as they self-reconstructed and drafted plans for recovery from centuries of enslavement.

One of these neighborhoods was called Bass Street. Located between the Edgehill and Cameron-Trimble neighborhoods at the foot of St. Cloud Hill between Fort Negley and the city, the Bass Street Community was formed by Black Civil War veterans and their families and other refugees from enslavement. Like most postwar communities, the residents embraced the ideals of community. Many worked at the Tennessee Central Railway (you’ll find some of their information from TCR employment records in the database) and enrolled their children in the nearby Pearl Jr. High (renamed the Cameron school in 1928) or at Fisk University. They worshiped at the Bass Street Church, which they had built together with their own hands. This church still exists today in its third location on Brick Church Pike in Northeast Nashville. Several of the Bass Street descendants who attended the original church as children remain members today.

When the federal government abandoned Reconstruction, it left this population to fend for itself during the Jim Crow era. By then, the Fort had become a symbol of Union occupation, Black self-determination, and federal power, and this divided the city. A local chapter of the white supremacist group, the Ku Klux Klan, made frequent appearances and attacks at the Fort, threatening the people who lived nearby. A group of Black Civil War veterans led by Leander Woods, who had served in the Battle of Nashville with the 13th USCT, Company E, had retained their wartime weapons for emergencies such as this, and engaged Klan members in armed combat in defense of Bass Street residents.

Throughout our fraught history, Black Nashville has always advocated for Fort Negley. Even as the city allowed it to fall into disrepair, Black Nashvillians never forgot. Though the city has lost the latest generation of the fort’s advocates, the team and advisory board here at the Builders and Defenders database wanted to take a moment to thank the late Mother Zula Usury, “Ghetto Joe” Kelso, Professor Bobby Lovett, Professor Reavis Mitchell, and Kwame “Leo” Lillard, among many others, for picking up this history and uplifting the descendants of the fort in the 1960s, 70s, 80s, 90s, and well into the 2000s. May they rest in power.

These activists and community organizers worked with some of our city’s Civil Rights leaders to preserve the fort’s legacy: James “Tex” Thomas, Curlie McGruder, Representative Harold Love Sr., Dr. Dogan Williams, Councilman Mansfield Douglas, Howard Jones Sr., Reverend Enoch Fuzz, Reverend Marcel Kellar, Deloris Wilkerson, Reverend Dr. Charles Kimbrough, Reverend Marilyn, Dr. Watts, and Alvin Futrell.

Without their tireless advocacy and work to remind us all of the city’s history, there might not have been anyone left to fight for the space when parts of Fort Negley Park were sold to make room for developments in 2017. The Builders and Defenders database team and its board would like to uplift these names and this legacy.

Fort Negley and the population that has descended from the enslaved and free Black people who built and defended it have seen many changes in the city. What hasn’t changed is the city’s unquenchable thirst for the history. The people and information in this database help to connect the story of the nearly 20,000 African Americans who made history at Fort Negley with the wider history of the city, the state, the region, the nation, and the world. The historical themes seen at Fort Negley (enslavement, impressment, resistance, revolt, emancipation, evolving notions of freedom, self-reconstruction, recovery, citizenship, communitarianism, education, nation-building, etc.) are themes that echo in every part of the globe where slavery of African captives and their descendants was legal.

When the federal government abandoned Reconstruction, it left this population to fend for itself during the Jim Crow era. By then, the Fort had become a symbol of Union occupation, Black self-determination, and federal power, and this divided the city. A local chapter of the white supremacist group, the Ku Klux Klan, made frequent appearances and attacks at the Fort, threatening the people who lived nearby. A group of Black Civil War veterans led by Leander Woods, who had served in the Battle of Nashville with the 13th USCT, Company E, had retained their wartime weapons for emergencies such as this, and engaged Klan members in armed combat in defense of Bass Street residents.

Throughout our fraught history, Black Nashville has always advocated for Fort Negley. Even as the city allowed it to fall into disrepair, Black Nashvillians never forgot. Though the city has lost the latest generation of the fort’s advocates, the team and advisory board here at the Builders and Defenders database wanted to take a moment to thank the late Mother Zula Usury, “Ghetto Joe” Kelso, Professor Bobby Lovett, Professor Reavis Mitchell, and Kwame “Leo” Lillard, among many others, for picking up this history and uplifting the descendants of the fort in the 1960s, 70s, 80s, 90s, and well into the 2000s. May they rest in power.

These activists and community organizers worked with some of our city’s Civil Rights leaders to preserve the fort’s legacy: James “Tex” Thomas, Curlie McGruder, Representative Harold Love Sr., Dr. Dogan Williams, Councilman Mansfield Douglas, Howard Jones Sr., Reverend Enoch Fuzz, Reverend Marcel Kellar, Deloris Wilkerson, Reverend Dr. Charles Kimbrough, Reverend Marilyn, Dr. Watts, and Alvin Futrell.

Without their tireless advocacy and work to remind us all of the city’s history, there might not have been anyone left to fight for the space when parts of Fort Negley Park were sold to make room for developments in 2017. The Builders and Defenders database team and its board would like to uplift these names and this legacy.

Fort Negley and the population that has descended from the enslaved and free Black people who built and defended it have seen many changes in the city. What hasn’t changed is the city’s unquenchable thirst for the history. The people and information in this database help to connect the story of the nearly 20,000 African Americans who made history at Fort Negley with the wider history of the city, the state, the region, the nation, and the world. The historical themes seen at Fort Negley (enslavement, impressment, resistance, revolt, emancipation, evolving notions of freedom, self-reconstruction, recovery, citizenship, communitarianism, education, nation-building, etc.) are themes that echo in every part of the globe where slavery of African captives and their descendants was legal.

Fort Negley Park is a UNESCO site of memory on the Routes of Enslaved Peoples (formerly the “slave route”). The international community has recognized it as a place where the most important themes of our shared pasts have played out and are being rediscovered thanks to the hard work and stewardship of a dedicated alliance of descendants, educators, public historians, civil servants, and community organizers. Fort Negley was a birthplace of freedom, and its complex and inspiring history connects Nashville to the wider world. It is a site that allows us to imagine better futures and to create a more equitable world moving forward.

Fort Negley Park is a UNESCO site of memory on the Routes of Enslaved Peoples (formerly the “slave route”). The international community has recognized it as a place where the most important themes of our shared pasts have played out and are being rediscovered thanks to the hard work and stewardship of a dedicated alliance of descendants, educators, public historians, civil servants, and community organizers. Fort Negley was a birthplace of freedom, and its complex and inspiring history connects Nashville to the wider world. It is a site that allows us to imagine better futures and to create a more equitable world moving forward.

Sponsored By: